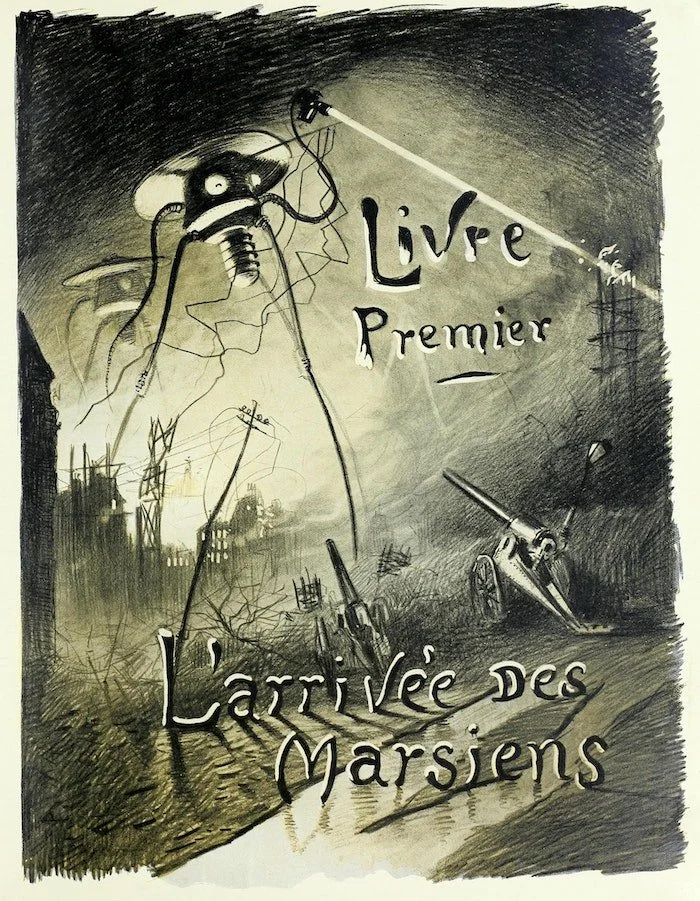

H.G. Wells: Dreaming of The Future

H.G. Wells is best known for the big ideas—time travel, alien invasions, invisibility—but those are just the surface. Underneath, his fiction is often working through something else: how society functions, and what might happen if it stops

H.G. Wells is best known for the big ideas—time travel, alien invasions, invisibility—but those are just the surface. Underneath, his fiction is often working through something else: how society functions, and what might happen if it stops.

Even in early novels like The Time Machine, the setup is more than just sci-fi curiosity. The split between the Eloi and the Morlocks isn’t random—it’s a way of thinking about inequality, industry, and what happens when progress loses direction. Wells wasn’t just imagining futures—he was examining the present through different lenses.

That becomes clearer when you read New Worlds for Old (1908), his direct case for socialism. It’s not radical in tone, and it’s not a call to revolution. What he outlines instead is a kind of organised, modern system built on fairness, planning, and collective responsibility. He thought society could run better if it actually tried to.

Wells’ version of socialism was more practical than ideological. He believed in science, education, infrastructure—and fiction as a way to make large ideas digestible. To him, storytelling wasn’t a distraction from real issues. It was a way into them.

Some readers pushed back. Orwell, for example, admired Wells’s early work but criticised what he saw as overconfidence in experts and systems. That tension—between imagination and idealism, between vision and control—is part of what makes Wells still relevant. He didn’t always get it right, but he was asking serious questions.

If you’re interested in seeing where his head was beyond the fiction, New Worlds for Old is a key text. It shows Wells not just as a novelist but as a social thinker—one who thought the future could be designed.

In case you haven’t already guessed, we’ve just added a first edition (early printing) to our shelves…

Comrade Mouse

It’s easy to imagine Eisenstein—the theorist of dialectical montage, the director of Battleship Potemkin—as someone too serious for cartoons. But in Notes of a Film Director, he spends several pages thinking quite seriously about Walt Disney.

Now in stock: Notes of a Film Director, Sergei Eisenstein. 1959 edition

It’s easy to imagine Eisenstein—the theorist of dialectical montage, the director of Battleship Potemkin—as someone too serious for cartoons. But in Notes of a Film Director, he spends several pages thinking quite seriously about Walt Disney. The Soviet filmmaker, who shaped the visual language of revolutionary cinema, was fascinated by the elastic, unpredictable world of Mickey Mouse. He even went so far as to call Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (1937) “the greatest film ever made”.

What drew him in wasn’t the sentimentality or the cheerful plots. It was the movement. Disney’s animation, he thought, achieved something close to pure cinema: transformation unbound by physical limitations. A character could dissolve, bend, reform. Shapes could rebel against realism. This wasn’t just amusing—it was, for Eisenstein, technically radical.

There’s something ironic here. A filmmaker who spent his career working within strict ideological frameworks praising the plastic freedom of Disney’s America. But Eisenstein wasn’t concerned with national labels—he was looking at form. He saw in Disney’s animation a kind of visual thinking that aligned with his own interest in metamorphosis, rhythm, and conflict on screen. So then the surprise isn’t that he liked Disney. The surprise is how closely he studied him.

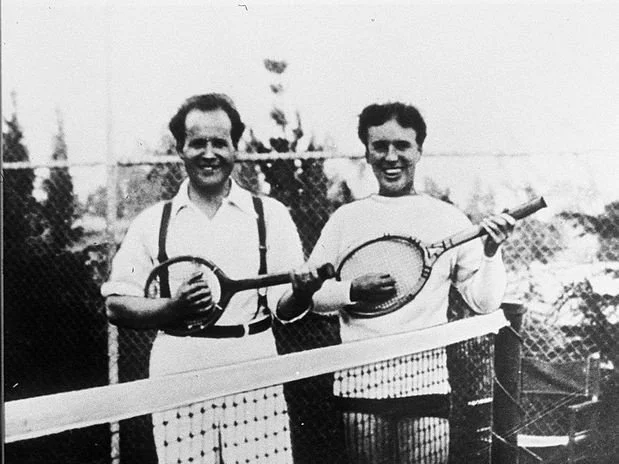

Sergei Eisenstein (left) and Charlie Chaplin (right) pretending to play a tennis racquet (1930).