Comrade Mouse

Now in stock: Notes of a Film Director, Sergei Eisenstein. 1959 edition

It’s easy to imagine Eisenstein—the theorist of dialectical montage, the director of Battleship Potemkin—as someone too serious for cartoons. But in Notes of a Film Director, he spends several pages thinking quite seriously about Walt Disney. The Soviet filmmaker, who shaped the visual language of revolutionary cinema, was fascinated by the elastic, unpredictable world of Mickey Mouse. He even went so far as to call Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (1937) “the greatest film ever made”.

What drew him in wasn’t the sentimentality or the cheerful plots. It was the movement. Disney’s animation, he thought, achieved something close to pure cinema: transformation unbound by physical limitations. A character could dissolve, bend, reform. Shapes could rebel against realism. This wasn’t just amusing—it was, for Eisenstein, technically radical.

There’s something ironic here. A filmmaker who spent his career working within strict ideological frameworks praising the plastic freedom of Disney’s America. But Eisenstein wasn’t concerned with national labels—he was looking at form. He saw in Disney’s animation a kind of visual thinking that aligned with his own interest in metamorphosis, rhythm, and conflict on screen. So then the surprise isn’t that he liked Disney. The surprise is how closely he studied him.

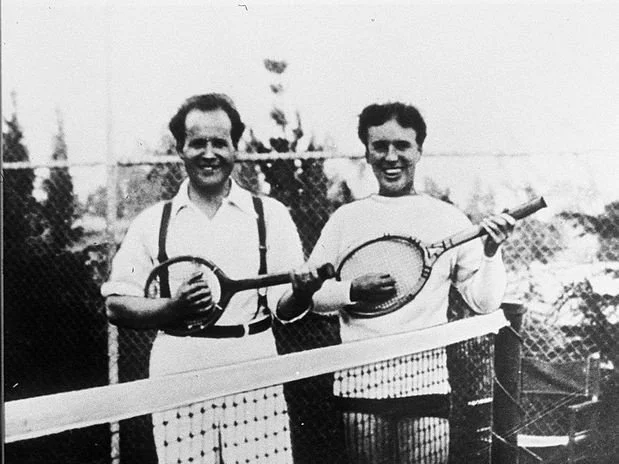

Sergei Eisenstein (left) and Charlie Chaplin (right) pretending to play a tennis racquet (1930).